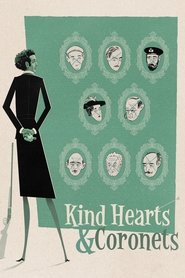

When his mother eloped with an Italian opera singer, Louis Mazzini was cut off from her aristocratic family. After the family refuses to let her be buried in the family mausoleum, Louis avenges his mother's death by attempting to murder every family member who stands between himself and the family fortune. But when he finds himself torn between his longtime love and the widow of one of his victims, his plans go awry.

Nine times out of ten, what is referred to as a matter of "some delicacy" is one of extreme indelicacy...

It just occurred to me that this is essentially another 'eat the rich' narrative similar to those popular today, and like those films, they don't actually wish to actually dismantle the system upon closer inspection but rather replace those at the top with people more likeable and deserving. (And who is more deserving than Alec Guinness?)

Anyway, on this watch, the noir elements stuck out a bit more, but it also showed how well hidden they are behind the port decanters and white tie. The ending was also more surprising: we are so used to Code-era movies needing the murderer to get his comeuppance (which the alternative US ending does…) that the dark conclusion that Louis will probably kill again is somewhat bleak, and furthermore stresses the noir element of the film. Also, remember that Louis also technically kills his own Dad as well, which probably should be counted in any tally of his deeds.

Capital crime has a strange transformative effect on Louis Mazzini. With each killing, his clothes become more stylish and luxurious. In the first reel of the picture, he is trapped in a shapeless lounge suit. Murder puts him in a pinstriped line and blazer, then a tightly tailored housecoat with lapels like a huge iridescent butterfly, and finally—in the condemned cell—he is resplendent in a smoking jacket with quilted silk roll collar.

— Matthew Sweet

[*Kind Hearts and Coronets* is an] Oedipal story […]. Simply by the shock of his entry into the world, Louis kills his father; he thereafter settles down into an exclusive loving relation with his mother. Lacking a father from this point, he can’t work through the Oedipal conflict: the fact that the same actor, Dennis Price, plays this cut-off father helps us to see the death in terms of what happens within Louis, as if what has died is a part of himself, of his psyche (it also, of course shows us Louis’s image of himself as married to his mother). […] The same principle applies, less speculatively, to the D’Ascoyne relatives, all eight being incarnated by Alec Guinness, like a monstrous father-figure whose power is belatedly encountered as Louis emerges, mother-dominated, into manhood and who recurs with the same face, time after time, Hydra-like as if in his nightmare.

— Charles Barr: Ealing Studios: A Movie Book

The ostensibly Edwardian London of th[is] postwar film is not really a place at all. It is a pastiche of a reverse fairy tale, where everything goes impeccably right until it goes neatly wrong; where everyone has the witty lines mere humans only dream of.

— Michael Wood (London Review of Books)