2002’s The Eminem Show [was] the album that vaulted him to a new plane of respectability—his flow was on a string like a child’s yo-yo. [A]nyone who thought that Eminem was just a foul-mouthed shock artist should have been astonished at his mechanical breath control and songwriting talent. This was no Eric Cartman; he was Picasso with food stamps.

In one [scene], Rabbit defends a gay co-worker, an obvious laundering of Eminem’s image after the fury over his homophobic lyrics and subsequent Grammy Award performance with Elton John.

As for that final battle scene—it understands both Eminem as a pop-cultural figure and Rabbit as a specific character, as well as the hidden aspects of what made Eminem radically fresh when he showed up. Part of Em’s tantalizingly wicked appeal was his extreme self-awareness; he comes from the same tree as 2Pac and LL Cool J with his emotional intelligence, which at times turns his acidic jokes inward. [I] have always had complicated feelings toward that line, and toward Eminem himself. Should this white man—who eventually became just as famous as, if not more than, the Black men he was challenging—be deified for this scene, for the complex that animated it? But in 8 Mile, Rabbit doesn’t score the uncomplicated victory over his doubters that it seemed, in 2002, Eminem had. After the battle is over, Rabbit goes back to the factory to finish out his shift. He doesn’t immediately get signed and get to make hit songs with Dr. Dre. For him—as for most of us—adulthood is going back to the grind after the very small accomplishments that you secretly suspect will change your life, but don’t.

— Jayson Buford (Los Angeles Review of Books)

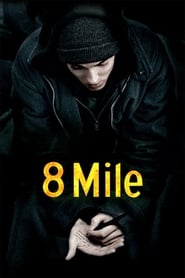

Synopsis: For Jimmy Smith, Jr., life is a daily fight just to keep hope alive. Feeding his dreams in Detroit's vibrant music scene, Jimmy wages an extraordinary personal struggle to find his own voice - and earn a place in a world where rhymes rule, legends are born and every moment… is another chance.