“At the movies, we are gradually being conditioned to accept violence as a sensual pleasure,” Kael complained, without recognizing that Burgess and Kubrick’s argument was precisely the inverse: violence-as-sensual-pleasure is a hardwired human trait, and attempting to deny or remove it in any kind of systematized way is a sign of a potentially fascist society.[…]

At times A Clockwork Orange plays like a critique of control-freakery made by a control freak. It also doesn’t help that McDowell’s charisma […] is emphasized at the expense of nearly every other character on screen. Those other characters are either depicted as ciphers or, worse, embodiments of petty-bourgeois ugliness who seem to invite or even deserve their own defilement.

[…]

What’s troubling about Kubrick’s film is that for all the big, abstract ideas it deals with, blame is not really one of them; instead, it sees our capacity for cruelty and carnage as innate and unchangeable, short of the most advanced, externally imposed mechanisms of denial imaginable. Kubrick loved these kind of big, archetypal ideas, sometimes to a fault, and a good deal of A Clockwork Orange represents the least appealing parts of Kubrick: the heaviness of his irony; the lugubriousness of his humor; the way he literally turns women into objects (the porcelain statuary at the Korova Milkbar); and the suffocating formalism of his style.

[…]

Is A Clockwork Orange Kubrick’s “worst”? The only thing that stops me from saying yes is the experience of re-viewing—and reviewing—a movie that tries to deal seriously with dark and twisted impulses in a moment when discussions about the virtues of art (specifically the possible “cancellation” of work that either contains unsavory content or has been produced by unsavory characters) have become a kind of moral pissing contest.

— Adam Nayman (The Ringer)

In 2022, speaking to Property Week, Kubrick’s American filmographer Alison Castle offered what is probably the most common contemporary understanding of [the Thamesmead] scene: “Kubrick’s choice of Thamesmead showed a very prescient instinct for how this architecture was deeply misguided and even hostile, doomed to fail as a model for living. As modernist as the buildings were, I believe he saw in them a dystopia.” [She] was reiterating an all-too-common contempt for other Sixties estates. But John Grindrod, Britain’s foremost chronicler of post-war modernism, saw something very different in that scene: “The town’s formal beauty, lakes and crisp white architecture were enhanced by his use of classical music to makes the scenes of sudden violence even more shocking and incongruous.”

— John Boughton (UnHerd)

The message of A Clockwork Orange was not pro-violence but anti-state – so plainly so that Kubrick must have felt ambushed when reviewers for the liberal papers called the movie fascist. The eruptive violence of an individual, this movie says, is a terrible thing, but the disciplinary violence of the state is worse.

— David Bromwich (London Review of Books)

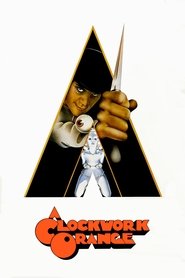

Synopsis: In a near-future Britain, young Alexander DeLarge and his pals get their kicks beating and raping anyone they please. When not destroying the lives of others, Alex swoons to the music of Beethoven. The state, eager to crack down on juvenile crime, gives an incarcerated Alex the option to undergo an invasive procedure that'll rob him of all personal agency. In a time when conscience is a commodity, can Alex change his tune?