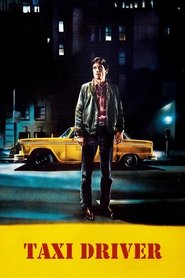

Watching this again for the third or fourth time, what strikes me is that it's less polished than I previously remembered. I can't point to anything in particular but, notwithstanding the nods to other directors being a trademark of budding filmmaker, it's a little more evident that this is part of Scorcese's early work.

Another thing that stood out was the scene in which Travis lazily kicks his TV over. If you take television to be some kind of symbol of purported respectable America, this scene shows that connection being severed. (And indeed, that is quite so: it's all downhill from that point.) But watch the destruction of the TV carefully, as it's not completely clear at all whether he destroyed the TV deliberately. To be sure, he is negligent in playing around with it like that, but haven't we all swung on our chairs like that? If so, then Travis' descent is at least very partly instigated by chance and circumstance. That also seems true to life when I think of the history of other reactionary nutjobs' histories.

This watch also made me much more sympathetic to the idea that the coda 'is a fantasy'. It was more noticeable to me this time as I focused on the bit where Travis (the avatar per excellence of wounded masculinity) pulls an unfathomable 'win' over Betsy being able to finally get her attention but being able to reject her. To someone like Travis (and many other men), the other thing better than getting laid by an attractive woman is being able to reject her.

Still, every scene is iconic; even the 'filler scenes' here and there are iconic. The opening is ironic. The colour scheme is iconic. The posters are iconic. The emphasis on 'We are the people' are iconic. Even Travis' horrendous meals are iconic. Yet it doesn't seem to damage the film at all.

I still find Jodie Foster's performance amazing. (Unrelated, but is Chloë Sevigny the Jodie Foster of the next generation down? She has a very similar face shape; was a child actor; and had roles that required them to be emotionally and sexually exposed at a very young age indeed.)

One last thing: it's always been a mildy exasperating to read commentators play down Travis' obvious racism by citing his claim in voiceover that "I work the city, up, down, don't make no difference to me." Notwithstanding that his very next line contains a racial slur, it is difficult to maintain that interpretation when (at least) the first two acts of the film depict Travis' attempts to fit in to society by saying the 'right' thing.

When shown on television, the ending credits featured a black screen with a disclaimer mentioning that "the distinction between hero and villain is sometimes a matter of interpretation or misinterpretation of facts." This disclaimer was thought to have been added after the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in 1981, but in fact, it had been mentioned in a review of the film as early as 1979.

[John Hinckley Jr.'s] action assured Taxi Driver a privileged position in cultural history, making it the only film to inspire directly a presidential assassination attempt. That the assassination failed is only fitting, since Taxi Driver is a film steeped in failure – the US failure in Vietnam, the failure of the 1960s counterculture and, most unnerving, at least to forty-nine per cent of the population, the failure of masculinity as a set of behavioural codes on which to mould a life.[…]

Taxi Driver as an attempt to reclaim – for the embattled white male – the urban landscape that had been revitalised by the blaxploitation films of the early 1970s. [Indeed,] the entire cast of Superfly (1972) seems to have been assembled in Times Square.

[…]

Taxi Driver’s appeal has something to do with the fact that Travis is largely a cipher that each viewer decodes with her or his own desire, and, also, with the fact that the more reprehensible aspects of Travis’s character are played down by the film.

[…]

What makes Taxi Driver an ur-text for the independent film-makers of the 1980s and 90s is precisely its fraught relationship to an idealised Hollywood past.

[…]

What’s crucial [is] that Travis’s encounter with Sport immediately follows his encounter with Palantine. Henceforth, they’re associated in Travis’s warped psyche – two men whom he resents because they hold women in thrall.

[…]

Among the many remarkable aspects of De Niro’s performance is the way he continues to suggest until the very end that we haven’t yet seen the worst of Travis. In this scene [in which he fights someone in Palatine's offices], Travis is still trying to hold himself together. It’s like watching someone trying to cork an exploding bottle.

[…]

Scorsese plays up the parallel between the triangle of Travis, Sport and Iris, and that of Ethan, Scar and Debbie in The Searchers. Travis, the cowboy, comes to rescue Iris, the maiden, whom Sport, the Indian, has defiled. [In a later sequence we see that] Travis needs to be saved as much as Iris does, and for a moment it seems possible for him to forge with her the friendship that he desperately needs.

— Amy Taubin: BFI Film Classics: Taxi Driver (2000)

By its final credits, Taxi Driver has reminded us that, depending on the public’s and the media’s mood, a Charles Manson or Charles Whitman or John Hinckley can also become an American hero—as exemplified by the idolatrous followings of My Lai’s William Calley and New York’s subway vigilante, Bernhard Goetz.

— https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/818-taxi-driver Frank Rich (Criterion)

[The] interface of art and business is fundamental to the achievement of [Bernard Herrmann's] Taxi Driver score, which helps disguise or at least rationalize the film’s ideological confusions, all of which circulate around the psychotic hero, Travis Bickle (De Niro). It assigns [him] an emotional purity that nothing else in the movie expresses — an emotional purity that coalesces around two contrasting themes that are endlessly reiterated and juxtaposed.[…]

It should be stressed that Schrader’s script — a grim, confused reflection of his strict upbringing as a Dutch Calvinist in Grand Rapids, Michigan […]— is a twisted self-portrait that sorely needs the realistic inflections and star power furnished by De Niro and the seductive fantasy elements conjured up by Herrmann (emotional) and Scorsese (visual). Without their contributions the story of Taxi Driver would be deficient in conviction and overall appeal, for a surprising number of details are implausible from the outset.

[…]

Taxi Driver takes a first step toward the mainstream gallows humor that will peak in Hannibal Lecter’s lewd winks in The Silence of the Lambs.

[…]

In short, thanks to what can only be termed the transformation of Taxi Driver‘s experimental and European elements into razzle-dazzle Hollywood effects, the spectator is invited to identify with a violently Calvinist, racist, sexist, and apocalyptic fantasy, complete with extended bloodbath, that’s given all the allure of glittering expressionist art and involves very few moral consequences for most members of the audience.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader)

With its nervous-generous hoopla of techniques (including the tic of flicking suddenly to a ceiling shot directly down on a seduction, gun sale, or bloodbath episode), almost every moment of a lumpen figure’s [Travis] hellish career has an assaulting quality, like a gnat banging suicidally against the light fixture.[…]

Unlike the unrelentingly presented worm in Dostoevsky's Underground Man, this handsome hackie is set up as lean and independent, an appealing innocent. The extent of his sexism and racism is hedged. While Travis stares at a night world of black pimps and whores, all the racial slurs come from fellow whites. In fact, Travis tries to pick up a mulatto candy seller in an interesting porno-theater scene. [Indeed,] Taxi Driver is always asserting the power of playing both sides of the box-office dollar: obeisance to the box-office provens, such as concluding on a ten-minute massacre, a sex motive, good guys vs. bad-guys violence, and casting the obviously charismatic De Niro to play a psychotic, racist nobody. [On] the other coin side, it’s ravishing the auteur box of Sixties best scenes, from Hitchcock’s reverse track down a staircase [to] the Frenzy brutality, through Godard’s handwriting gig flashed across the entire screen […].

— Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson (Film Comment)