The Godfather is like a wonder of the world about which you have read everything, which you finally get to see, about which you utter a few clichés from a tourist guide on your return, and about which it is hard to say anything meaningful.

— Peter van Bueren (De Tijd, 1972)

It is a principal thesis of The Godfather that American society is a Gesellschaft at war with the Gemeinschaft inherent in the extended families of organized crime, and it is the claim of the novel and even more intensely of the films that the truly natural, legitimate, normal, and healthy type of society is that of the gangs. [It] offers a powerfully pessimistic (some might even say cynical) view of man and society that slaps in the face the pleasanter views characteristic of modernist ideologies drawn from the doctrine of progress and especially the favorite American myth that through assimilation into the institutional environment offered by the democratic capitalism of the American Gesellschaft, human beings can be perfected and force and fraud as enduring and omnipresent elements of social existence can be escaped.

— Samuel Francis (Chronicles)

The key to The Godfathers and to success in the Mafia genre is the realization and dramatic portrayal of the fact that the Mafia, although leading a life outside the law, is, at its best, simply entrepreneurs and businessmen supplying the consumers with goods and services of which they have been unaccountably deprived by a Puritan WASP culture. […] Organized crime is essentially anarcho-capitalist, a productive industry struggling to govern itself; apart from attempts to monopolize and injure competitors, it is productive and non-aggressive.[…]

The father [Bonasera] whispers in the Godfather’s ear. “No, no, that is too much. We will take care of him properly.” So not only do we

see anarcho-capitalist justice carried out, but it is clear that the Mafia code has a nicely fashioned theory of proportionate justice. In a world where the idea that the punishment should fit the crime has been abandoned and still struggled over by libertarian theorists it is heart-warming to see that the Mafia has worked it out in practice.

As with Macbeth, you can endlessly change your mind about whether Michael Corleone is a sociopath all along, or whether he is made evil by circumstance. Pacino argues that the character only fully becomes himself after his father is shot. In the thrilling scene when he goes to the hospital to stand watch over Vito, he is ‘still not quite Michael’, Pacino says; he only starts to recognise his own authority when he sees that the hand of Enzo the baker, the only person there to help him, is shaking whereas his own hand is still. In the first week and a half of filming Pacino deliberately did almost nothing with the character, trying to indicate that he wasn’t yet the terrifying person he would become by the end. But this downplayed acting made the execs at Paramount question whether he was right for the part. Coppola took him to one side to warn him that he was ‘not cutting it’ and moved forward the filming of the scene in which Michael kills two of his father’s enemies in a restaurant to reassure the studio that Pacino had what it took.

— Bee Wilson (London Review of Books)

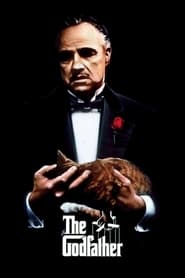

Synopsis: Spanning the years 1945 to 1955, a chronicle of the fictional Italian-American Corleone crime family. When organized crime family patriarch, Vito Corleone barely survives an attempt on his life, his youngest son, Michael steps in to take care of the would-be killers, launching a campaign of bloody revenge.