Reviewing The Silence of the Lambs over 16 years ago, I was troubled by the way the thriller tapped into “irrational, mythical impulses that ultimately seem more theological than psychological,” and how critics who loved it seemed “better equipped to regurgitate the myth than to analyze it.I was especially bemused by the ready acceptance of Hannibal Lecter’s supernatural powers — his ability to convince a hostile prisoner in an adjoining cell to swallow his own tongue, for instance, or to know precisely when and where to reach Clarice, the movie’s heroine, on the phone. Anthony Hopkins’s Oscar-winning performance may be stark and commanding, but it wouldn’t have counted for beans if the audience hadn’t already been predisposed to accept this murderer as some sort of divine presence.

The waves of love that went out to Lecter, epitomized by the five top Oscars the movie received in 1992, were a mix of giggly fascination, twisted affection, and outright awe for his absolute lack of remorse. This was during the first Gulf War, a time when we were grappling with our own feelings about killing masses of people on a daily basis. I suspect Lecter represented a savior of sorts, a saintlike holy psycho who made us feel less uneasy about wanton slaughter.

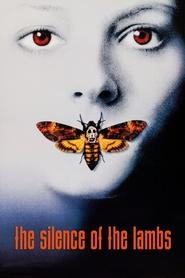

Synopsis: Clarice Starling is a top student at the FBI's training academy. Jack Crawford wants Clarice to interview Dr. Hannibal Lecter, a brilliant psychiatrist who is also a violent psychopath, serving life behind bars for various acts of murder and cannibalism. Crawford believes that Lecter may have insight into a case and that Starling, as an attractive young woman, may be just the bait to draw him out.