Business being equated to gangsterism is hardly a new idea in film, but it's rarely been pulled off so strongly and presciently. Although it shows its age and low-budget today, it’s remarkable how clearly this film predicts the London Docklands property boom, the quasi-gangster undertones of Thatcherism as well as Britain's post-Imperial desire to be at the centre of an increasingly globalised economy. Had to chuckle at the reference to "the 1988 London Olympics," knowing that it foreshadows what would happen around Stratford and Hackney Wick in 2012. It also 'predicts' much of the tenor of future gangster films as well — I challenge anyone not to see the character of Jimmy Price in Matthew Vaughn's Layer Cake (2004), another film that successfully engages with the later New Labour political economy whilst being highly entertaining at the same time. Someone should make a 'third' film today about a supply-chain constrained post-austerity London.

Obviously, Hoskins is holding The Long Good Friday together, and Peter Bradshaw is right when he claims that "Hoskins’ bullish, black-comic Napoleonism makes this movie: pugnacious, sentimental, a cockney [James] Cagney." Absolutely love Pierce Brosnan's shit-eating grin in the final scene—which rivals the ending to Knife in the Water (1962)—as well as that he's credited as "First Irishman," which should be the name of his memoir.

The director […] uses an elegant stylistic effect to make [a] point, so that we get it subliminally before we are anywhere near working out its contours. The camera keeps arriving at a scene – a country cottage seen from a small distance, the interior of the same cottage glimpsed through its windows, a swimming pool, the pub that is about to be blown up – when nothing has yet happened there. The technique makes the very idea of seeing ominous.

[…]

Even the wonderful last frames of the film may leave us [without seeing]. Shand is shut up in the kidnappers’ car, a gun trained on him. Apart from occasional glances at the gunman’s face, the camera just watches Shand in close-up for more than two minutes. At first he seems to grin in a troubled fashion, ready to think his way out of this spot, then his face settles into worry, and then into a kind of blank. It is this blankness that allows us to think he may finally have understood who or what his new enemies are; have glimpsed the pathetic, failing range of his old methods and the emergence of the new world.

— Michael Wood (London Review of Books)

Hoskins does more with his cheeks and jowls than Richard Nixon: He makes the curve of his teeth look as ominous as a crossbow, and trains his eyes like gun sights on his targets. [He] has the gift usually attributed to American, not English, actors—of getting so far inside a character’s skin that we seem to be witnessing vivid behavior rather than bravura performance.

— Michael Sragow (Criterion)

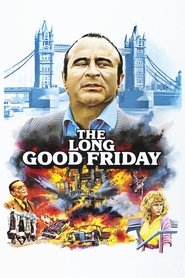

Synopsis: In the late 1970s, Cockney crime boss Harold Shand, a gangster trying to become a legitimate property mogul, has big plans to get the American Mafia to bankroll his transformation of a derelict area of London into the possible venue for a future Olympic Games. However, a series of bombings targets his empire on the very weekend the Americans are in town. Shand is convinced there is a traitor in his organization, and sets out to eliminate the rat in typically ruthless fashion.