The scenes of Brady taming horses are worth the runtime, as are any and all scenes featuring Lilly and Lane. Indeed, the merging of fiction and non-fiction distantly recalls Clint Eastwood's 15:17 to Paris (2018), a film that continues to haunt me for its neo-neorealistic casting strategy and subsequent tone. Although Nomadland did contain "Actual RV Nomads", this always felt like something too-tidily packaged for the film's publicity materails, and it is remarkable what a difference it is when this casting methodology is applied to the main character.

Speaking of allusions though, it is difficult to avoid Darren Aronofsky's The Wrestler (2008), and The Rider is alas deeply depoliticised in comparison. Zhao is not overly condescending to the Dakotan working class, though she does appear to stereotype them as taciturn and inarticulate. All a harbinger for her Academy-friendly Nomadland, perhaps. Brady's spiritual relationship to the animals also reminded me in parts of the horse-taming scenes from Cormac McCarthy's 1992 novel All the Pretty Horses; uncharacteristically unromantic sections from an author who "has spent forty years writing as if he were trying to expand the Old Testament".

Anyway, whilst the Malickian magic hour visuals of Dakota are visually stunning, they lack Malick's elliptical gaze and editing style, leading to the sense that there is a lack of deeper meaning being expressed. And effective as it might be, Malick would never have such a tidy metaphor of Brady finding his final horse by walking through the graveyard of rusted American cars á la the BBC correspondent in Nashville (1975).

The proximity of this fiction to actual fact adds an inherent layer of interest, especially in scenes between family members, which resemble the kinds of conversations they must have, or have had, about the real Brady’s accident and his high-risk life choices. But those opportunities aren’t seized on as directly as they could be; the writing instead emphasizes the universality of the family’s struggles, turning a potentially very personalized narrative into more of an archetypal one.[…]

In terms of its overall structure and the specifics of Brady’s post-accident life, it feels tidy and conventional. Jandreau’s presence should heighten the sense of realism here, but instead Zhao seemingly directs the first-time actor into being the laconic, brooding screen presence that this kind of film would normally call for.

— Sam C. Mac (Slant Magazine)

Movies that blend narrative and documentary [often] find ways to cordon off the fiction from the real life, winking at us when the boundaries have been crossed. Intentionally or not, such films become about the blurring of these lines. That has its place. But Zhao takes a different approach, privileging the narrative, the poetry, and the realism in equal measure.

— Bilge Ebiri (Village Voice)

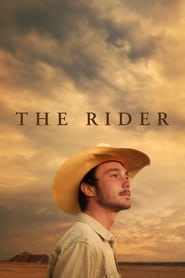

Synopsis: Once a rising star of the rodeo circuit, and a gifted horse trainer, young cowboy Brady is warned that his riding days are over after a horse crushed his skull at a rodeo. In an attempt to regain control of his own fate, Brady undertakes a search for a new identity and what it means to be a man in the heartland of the United States.