Frank is an expert professional safecracker and specialises in high-profile diamond heists. He plans to use his ill-gotten gains to retire from crime and build a life for himself with a wife and kids, so he signs on with a top gangster for one last big score.

This, of course, could be the plot to any number of heist movies, but Thief does something different. Similar to The Wrestler and a number of other films I watched this year, Thief seems to be saying about our relationship to work and family in modernity and postmodernity. Indeed, the heist film, we are told, is an understudied genre, but part of the pleasure of watching these films arises from how they portray our desired relationship to work. In particular, Frank’s desire to pull off that ‘last big job’ feels less about the money it would bring him but a displacement from or proxy for fulfilling a deep-down desire to have a family… or indeed any relationship at all. Because in theory, Frank could enter into a fulfilling long-term relationship right away, without stealing millions of dollars in diamonds. But that’s kinda the entire point: Frank needing just one more theft is an excuse to not pursue a relationship and put it off indefinitely in favour of ‘work’. (And being crimes, of course, it also means Frank cannot put down meaningful roots in a community.) All this is communicated extremely subtly in the lowkey diner scene, by far the outstanding scene in the entire movie.

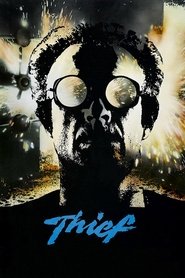

The visuals of Thief are as if you set the brilliant The Warriors (1979) in a similarly-filthy Chicago, with the Xenophon-inspired plot of The Warriors replaced with an almost deliberate lack of plot development… And the allure of The Warriors’ fantastical criminal gangs (with their alluringly well-defined social identities) substituted by a bunch of amoral individuals with no solidarity beyond the immediate moment. A tale of our time, you might say.

I must warn you that the ending of Thief is famously weak, but this is a gritty, intelligent and strangely credible heist movie before you get there.

The film was intended to be a political analog. The only body of criticism that got it were the French critics. Nobody here got it. Most American critics focused on the style of the movie. Some found it lovely, others empty. Almost nobody mentioned its politics. What’s driving Frank is Karl Marx’s labor theory of value. I saw one of the writers walking around during the Hollywood strike recently with that quote from Thief on a placard — “I can see my money is still in your pocket, which is from the yield of my labor” — which I was very complimented by.

— Michael Mann (Vulture, 2023)

Synopsis: Frank is an expert professional safecracker, specialized in high-profile diamond heists. He plans to use his ill-gotten income to retire from crime and build a nice life for himself complete with a home, wife and kids. To accelerate the process, he signs on with a top gangster for a big score.