Depressing movies with unhappy endings are often seen as offering a bracing contrast to the standard Hollywood fare. This may help explain the appeal of Brokeback Mountain, whose drafts of misery are seen by some people as daringly honest and authentic. […] I would argue that a certain complacency surrounds some of these doom-ridden scenarios, especially ones that suggest social change is impossible–a vested interest in the status quo, even conservatism, seems to lurk behind the apparent apoliticism.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader)

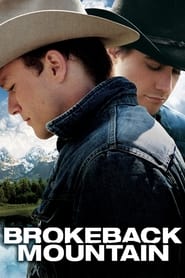

Even in a nascent social media moment, Brokeback Mountain was a lightning rod for critical discourse, with predictable saber rattling from right-wing talk radio types [and] some more than fair hand-wringing at the other end of the spectrum that a movie about the queer experience made by a straight director with a pair of heterosexual A-list leading men reeked of compromise. For the most part, though, Lee’s film was enough of an artistic success that it evaded the usual hysteria that followed movies about the gay experience. “What if they held a culture war and no one fired a shot?” wrote Frank Rich in The New York Times in December 2005.[…]

[A] film of massive establishing shots and horizon lines; the question of whether its painterly approach was meant to make its contents more palatable to a mainstream audience is worth asking. But considering that the main thrust of the story has to do with Ennis and Jack experiencing their summer under the stars as a kind of secular Eden, the gorgeousness of the imagery serves a rhetorical function.

[…]

Most of Lee’s movies could be retitled Lust, Caution, and not necessarily in that order.

— Adam Nayman (The Ringer)

For me, the fact that I still can’t fully square what the film is doing is a mark of its quality and, as often with this filmmaker, of Lee’s sense and sensibility.[…]

The close-up on Hathaway’s inscrutable face as Lureen tells Ennis the tire story is absolutely devastating. It’s as though that shot were imprisoning her in that tale, too–reducing this once vibrant, free-spirited woman to the tragic story she has to tell to make sense of what happened.

— Manuela Lazic (The Ringer)