Seattle International Film Festival 2023: Film #19

Just as Andrew is trying to find his own solution to the apparent binary betwixt 'boy' and 'girl', so is L’immensità is attempting to carve out a new space between the long-established genres of melodrama, the coming-of-age saga, pure audience entertainment and the heavy-handed issue picture. For the most part, the film manages to locate a gap, not least of all because of its preternatural ability to turn on a lira between a number of different moods and registers. This is true save for two extended moments of burlesque surrealism, which don't have the cathartic effect they strive for, and one of the film's key weaknesses is that it relies on these moments of exception for its most important moment.

The film is both light and heavy-handed in its use of symbolism. It is, of course, at its best when dealing with the former — I could have done without the on-the-nose explanations about the microbes and Andrew's father being such an obvious avatar for patriarchal male anger. Where it does better is in Andrew's asthma, for his difficulty in breathing is a symbolic manifestation of his inability to live comfortably and safely within his own skin, which flares up in a way not dissimilar to Winston Smith's varicose ulcer in Nineteen Eighty-Four troubles him differently depending on his situation. (Note also Andrew's dependence on an unhelpful medical establishment for medication and the dismissive attitude of its doctors, clearly alluding to the treatment of those wishing to medically transition.)

Equally light-touched is the traveller community who are camping close to the family's apartment block. Their subsequent removal by the state parallels the continued elimination not only of Roma communities today but also the erasure of trans identity and culture in a much broader sense. That Andrew suffers an acute asthma attack when he learns that the authorities have evicted the Roma by force is obviously no accident, as the Roma community subconsciously demonstrated to him that it was at least possible to live a life that was parallel to—or at least different from—a 'normal' one. It feels important, too, that Andrew's body feels this erasure first in the form of an asthma attack before his head comprehends what is going on. Of particular importance to this broader of Roma-as-minority metaphor is that their eviction was performed quietly, paralleling the erasure of LGBTQ+ voices from the cultural mainstream under our noses.

Penélope Cruz provides an objectively good performance, but it is the paratextual part of Cruz that intrigued me the most. In a way that I can't quite explain, she never stops looking like 'Penélope Cruz', so it is often hard to engage with her commendable performance as it exists on the screen. This peculiar difficulty of seeing beyond Cruz qua Cruz is then compounded by her character's mental illness, which perforce renders her slightly unpredictable. Saying that, is her character even ill? Andrew's mother, later healed by Western medicine, has been 'cured' of her central delusion (i.e. that Andrew is a girl), but she's more a victim of domestic violence. The later scene in the hospital car park is therefore a stationary car crash of sorts, as Andrew knows exactly what is coming but is still somehow shocked and devasted when his Mum deadnames him. Yet perhaps casting Cruz had a deeper purpose beyond adding a big name to the cast. To the extent that it is difficult to see beyond Cruz as anything but Penélope Cruz, so do L’immensità's characters find it difficult to look past Andrew's own body.

Clara is clearly heading for a terrible breakdown, and her behaviour certainly makes solid dramatic sense: but it is sometimes a bit ungainly and uneasy to see Cruz in these situations, which do not have the delicacy and subtlety of her work with [Pedro] Almodóvar.

— Peter Bradshaw (The Guardian)

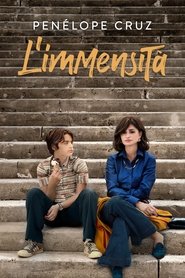

Synopsis: Clara and Felice struggle to raise their three children in 1970s Rome. The eldest, Andrea, is transgender and yearns for another life where he gets to live as the boy he knows himself to be. Clara instinctively strives to protect her son by escaping into their imaginations to defuse family tensions.