Films made with the Bresonnian 'transcendent' treatment are poised perilously on a knife-edge between being a masterpiece (like Pickpocket) and the result coming across as sterile and idiosyncratic to the viewer, full of perverse artistic choices that seem designed to frustrate the viewer. The Card Counter is, to me, on the wrong side of this line. Chuck Bowen on (Slant) observes that:

Schrader dries the plot of The Card Counter out, slowing it down and homing in on the repetition of inhabiting and sterile tourist traps for a living. [Indeed,] Schrader continually denies us routine pleasures, such as evolving character development, suspense concerning money lost or gained, the highs of winning, and sex appeal.

… whilst Lex Briscuso (Paste Magazine) seems even less taken by the movie given the broader context of Schrader's filmography:

There’s only so many times the same themes can be reinvented and dusted off as new. The notion that Schrader’s protagonists’ struggles mirror his own habitual revisitations isn’t lost on me. The one-note familiarity of The Card Counter ends up undermining rather than reinforcing everything we love about his work because ultimately, we don’t want a template if there’s no meat between the bones. Eventually, you have to turn a corner. Even the film’s ending ends up coming off as a misfired rehash of the euphoric moment that closes out First Reformed.

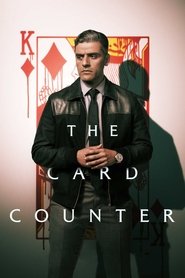

Synopsis: William Tell just wants to play cards. His spartan existence on the casino trail is shattered when he is approached by Cirk, a vulnerable and angry young man seeking help to execute his plan for revenge on a military colonel. Tell sees a chance at redemption through his relationship with Cirk. But keeping Cirk on the straight-and-narrow proves impossible, dragging Tell back into the darkness of his past.