— Maybe the nuns will be able to straighten you out.

I generally adore deadpan comedy, and all the ingredients were here for something I should enjoy — even putting the very 90s statutory rape subplot aside. But there was just something off about the combination of the film's execution and my mood that made this not work for me.

The film is portrayed primarily through the eyes of Mr McAllister's "bee-stung point of view" (Eric Henderson), but there are then four other characters who have their own say via voiceover narration. These additional sardonic viewpoints (which hit mostly the same comic notes) may be intended to be analogous to the mid-1980s deregulation of cable television that led to multiple media 'narratives' on the same events, each of them self-serving in their own way. But with the film's heavy reliance on the syntax of the teen movies popular in the last decade of the 20th century, this unexpected crowd of voices mostly came across as disorientating to me.

Indeed, it is well established that Election was "conceived in significant part as a reaction to the results of the 1992 presidential race, [and] a merciless burlesque of the impossibility for America to move beyond two-party partisanship." For me, though, the film's admirable allegorical intentions are blunted by the aforementioned use of teen movie genre trappings, not least because its political message is difficult to discern below its slightly confusing message: "Our protagonist sublimated reactionary response to a born leader who’s also female is, complicatedly, one that the film itself doesn’t exactly reject." These "complications" don't quite read as precisely-calibrated ambiguities than they do unnecessary provocations. It's not so much that the film has 'aged like milk', but it has dried out like old yeast.

Dana Stevens argues for the film in their 2017 retrospective which accompanies the Criterion release, astutely observing that "apples, the official fruit of both teacher appreciation and the temptation to sin, are a motif of the movie". Yet I can't quite bring myself to agree that the film is "played in a savage register unseen in American comedy since the days of Preston Sturges". Stevens provides some useful biographical info though:

In the original ending that Payne shot for Election, one that hews more closely to the conclusion of Perrotta’s novel, we find Mr. M. working at a car dealership and Tracy coming in to buy a car for college. The two of them go on a test-drive together, and he apologizes for his mistreatment of her during the election fiasco. As the film ends, she asks him to sign her senior yearbook, suggesting the beginning of a truce. It’s a much softer ending for a film that, for the preceding hour and a half, offered very little in the way of heartwarming emotional overtures. After test audiences, as well as the filmmakers themselves, reacted negatively to this scene’s incongruous tone of elegiac sweetness, Payne and Taylor wrote the darker ending and filmed it a few months before the film’s release.

Given that the film is a satire of the US electoral process, it is ironic (and perhaps even meta-allegorical) that the film's bitter ending was itself 'focus-grouped' and 'workshopped' into existence.

PS. It's kind of wild that this script originated from Tom Perrotta thinking that Bill Clinton was being unfairly treated due to his sexual history: "The Republican talking point was 'If he cheated on his wife, he's going to cheat on the country. It seemed like they were advancing this simplistic, moralistic philosophy about character. Something wasn't right about it."

It’s easy, when looking at the film 25 years after its release, [and] conclude that it’s a harbinger of the suppression of hyper-qualified female candidates in a patriarchal world. But, just like the political process [it’s] not a work that can be reduced to a few liberal signifiers. It’s a work that depicts the failures of the American political project, sure, but also a castigation of our collective hypocrisies—of the ways in which our repugnant, short-sighted impulses inform the malfeasance within political machinations.

— Hafsah Abbasi (Paste Magazine)

If Billy Wilder had been assigned to make a teen comedy, he might well have come up with a film as witty and sour as this.

— Geoffrey Macnab: Sight and Sound (1999)

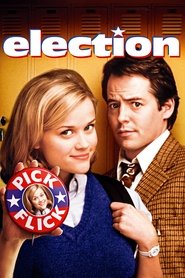

Synopsis: Tracy Flick is running unopposed for this year’s high school student election. But Jim McAllister has a different plan. Partly to establish a more democratic election, and partly to satisfy some deep personal anger toward Tracy, Jim talks football player Paul Metzler to run for president as well.