— You know, the lover I used to live with... He loved yogurt. He loved it, so I bought about thirty. I went into this supermarket in the neighborhood. I got nothing but yogurt. I remember I came staggering home with two huge bags... I thought, "Oh, wow, will he flip out when he opens the refrigerator..." But he said: "But Veronica, all this yogurt... That's a bit weird..." And me thinking he'd be so happy and all... "A bit weird... ".

We approach [the film] as if heading to a massacre…

— Philippe Azoury: Jean Eustache: Un amour si grand...

Eustache had transposed some of their lovers’ conversations into the script for his three-and-a-half-hour portrait of their fractious relationship, using tapes he had made with a recorder hidden under their bed. The young woman […] was aware of its scabrous real-life revelations, but its full emotional effect seemed to register only after she witnessed her character, the eponymous “mother,” recreated on-screen with such arrant fidelity. She wept throughout the screening, then left a note—“The film is sublime, leave it as it is”—before downing a bottle of barbiturates. […] Despite its unfashionable revanchism, the film quickly became the cardinal document of its disconsolate era, its final, abrupt image of Alexandre slumping to the floor in alarmed disbelief after a nauseous, intoxicated Veronika agrees to marriage emblematic of a social utopia that Eustache appears to think did not fail, but never was.

— James Quandt (New York Review of Books)

As Alexandre regularly monopolizes conversations to rant about oversexualized culture, the failure of progressive politics, and other such topics, a portrait of the young man emerges that’s possibly far more recognizable in 2023 than it was in 1973. Despite all of his sexual dalliances, Alexandre’s repressive views of women’s role as subservient to men and the manner in which he expresses these notions marks him as a prototype of the modern incel. Likewise, his apostasy from his supposed progressivism of his younger days recalls the increasingly common “post-left” figure who trollishly embraces the most reactionary politics possible as “true” rebellion. […] Of particular note is the way that Alexandre’s cinephilia, which he expresses amid his broader personal-political polemics, reinforces his conservative views instead of complicating them. […] Pauline Kael astutely saw Eustache a kindred spirit of John Cassavetes, namely in the way that this film’s main characters manage to reveal deep psychological insights through dialogue and behavior without resorting to the language or obvious gestural signifiers of psychology.

— Jake Cole (Slant Magazine)

Alexandre is smart enough, but not a great intellect. His favorite area of study is himself. […] We think of the cafes of Paris as hotbeds of fiery philosophical debate, but more often, I imagine, they are just like this: people talking, flirting, posing, drinking, smoking, telling the truth and lying, while waiting to see if real life will ever begin.

As Pauline Kael noted back in 1974, “It took three months of editing to make this film seem unedited.” Each sequence begins with a fade-in and ends with a fade-out, creating a ghostly overall texture that seems inseparable from the film’s complex relation to nostalgia. […] I was living in Paris when the film was shot and first released. My closest friend there was a sculptor and draft dodger from Watts who was supported by the older French woman he lived with, and he cheated on her even more than Alexandre cheats on Marie. However much one might disapprove of this sort of arrangement, it was tolerated and even sanctioned by Parisian culture in much the same way that the intellectual jabber was — less encumbered by puritanism and feminism and ultimately protected by a profound belief in pleasure motored by male entitlement. […] In the final analysis, The Mother and the Whore is in love with the idea of defeat; that is its reactionary strength, and most of what I cherish as well as mistrust about the film derives from this fact. […] Deconstruction [of Leaud's acting career] is partially echoed by subtle but radical shifts in the film’s narrative viewpoint. Our last look at Marie, when she’s listening to Piaf, is the first time the film shows us something Alexandre doesn’t see, and a brief moment with Veronika alone in her room shortly afterward is the second. The moment Alexandre loses his omnipotence as implicit narrator, he loses part of his status as hero as well.

When The Mother and the Whore was rereleased in Paris in the spring of 2022, it achieved 30,000 admissions in a dozen screens. At one cinema, it was more successful than its direct rival Top Gun: Maverick.

— David Thompson (Sight and Sound)

According to the French journalist Muriel Zagha, the French censors gave Eustache's film an 18-only certificate not for the rain of F-bombs, but bbecause its long soak in nihilism might prove hazardous to the young and impressionable. That might've been wise; are any of us invulnerable to it?

— Michael Atkinson (Sight and Sound, Winter 2024)

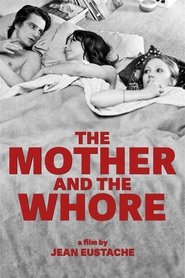

Synopsis: Aimless young Alexandre juggles his relationships with his girlfriend, Marie, and a casual lover named Veronika. Marie becomes increasingly jealous of Alexandre's fling with Veronika and as the trio continues their unsustainable affair, the emotional stakes get higher, leading to conflict and unhappiness.