Sembène knew his cinema, so I suspect that the name is also a reference to The Earrings of Madame de... (1953) by Max Ophüls.

Focused on literature, [director Sembène] published ten novels, but he soon realized that language, with its myriad of potential translations and rampant illiteracy, was a limiting factor in the number of people he could reach. At 40, he went to film school and learned filmmaking, hoping the new medium would allow him to reach a wider audience.[…]

Because Sembène never received the correct authorization, the film, which was originally supposed to be a 90-minute feature, was cut short to qualify La noire de… as a longer-than-usual short film. The shorter length (59 minutes) allowed Sembène to circumvent some of the bureaucracy associated with the Bureau du Cinéma and CNC’s policies. […] The extent to which Sembène was forced to work in and financially depend on France’s bureaucratic system of production, despite being a citizen of independent Senegal, strangely mirrors Diouana’s economic dependence on her employers.

[…]

Had Sembène been allowed to make the film as originally intended, he would have created an effect similar to MGM’s The Wizard of Oz (1939), wherein the mythical land of Oz (in this case France) was in color, while other scenes were in monochrome—but in Sembène’s vision, Diouana would have discovered that the shining myth of France was untrue. Nevertheless, his allegory remains sound. He intentionally uses generalized types for his characters to create a political association by which the characters are understood. His French characters have no particular or defining characteristics beyond their race and national identities, but then neither does Diouana. The entirety of France, too, is an obscure object of desire—a myth that remains unattainable.

[…]

Until the very end, Dakar is only seen through Diouana’s memory-images. These images are not flashbacks in the way that we normally think of them. They are not products of the filmmaker taking us into Diouana’s past to provide us with important narrative information. Instead, they are images projected onto the screen from Diouana’s memory. Dakar has a place in her memory alone […].

[…]

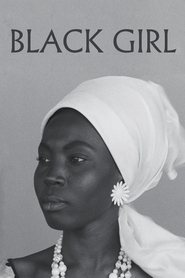

Calling the film “Black Girl” is misrepresentative of both the film and the original title. The “de…” of the title is a preposition followed by an ellipsis, suggesting an unknown place of origin, reflecting Diouana’s displacement and fragmented identity in her postcolonial world. By contrast, the English title presents a closed case, its absoluteness determined by its lack of ambiguity. It tells us who she is: a black girl—complete, her origin unquestioned. The French version suggests that black bodies are almost innately sites for cultural fragmentation due to a global history of colonialism and slavery.

— Brian Eggert (Deep Focus Review)

Funding constraints forced Sembène to dub Diouana’s minimal yet poetic interior monologue in French, a compromise that has the powerful dramatic effect of reflecting the psychic weight of colonialism: she must craft her inner self in a language she cannot speak.[…]

Diouana is […] subjected to overt racism in dinner party scenes set around her employers’ dining table; these are horrifying due to their blank understatement. [The] guests—clearly well-to-do “liberals,” by the way—speak patronizingly of Africans in Diouana’s presence (“With independence, the natives have lost a natural quality”).

[…]

One solitary, charged glance between Diouana and the husband, midway through the film, is enough to suggest that a similar psychosexual panic has taken root in the wife’s mind, precipitating her increasingly heinous behavior. It is notable, though, that Sembène has empathy for the pathetic creature he has created for Jelinek to play. Were the film being made through a Eurocentric, perhaps a Godardian lens, that character would likely be its focal point: an anthropomorphized slab of breathy ennui, undesired sexually by her husband. Through Sembène’s eyes, however, the focus has shifted entirely.

[…]

The ellipsis after the preposition [in the film's title] leaves unspecified whether de means “from”—as in coming from a specific place—or the possessive of, which reduces Diouana to the status of property. Both interpretations are appropriate; the distinction becomes academic in the light of the character’s swift decline and suicide—a definitive act of spiritual reclamation.

[…]

In an electrifying coda, the mask finds its way into the hands of a young boy there, and becomes a totem of anti-assimilationist sentiment, vibrating with pro-African resistance; it seems to almost literally propel a frantic Monsieur back toward the airport. In [La noire de…]’s closing moments, then, a desperately sad saga is transformed into a transcendent howl of hope for a new Africa.

— Ashley Clark (Criterion)

The mask from Black Girl is the key that connects past, present, and future generations, all still haunted by colonialism.

— Vlad Dima: Everything Begins in the Middle: Xala and Futurity (Film Quarterly)