I felt that I had seen this movie before ("oh, it's this scene!"; "oh, it's that guy!"), yet it turns out that it's been source material for decades of teen movies. And turning it around, I'm sure I saw the prototype for pseudo-womaniser Damone in Jean Eustache's superb post-1968 La Maman et la Putain [1973].

Dana Stevens writes that:

This is the story of one fifteen-year-old girl’s clumsy and sometimes painful introduction to the world of sex, related without judgment or preconception or the least hint of sentimentalization.

Perhaps this is missing some kind of negative adjectival modifier before "judgment," because surely the lack of disapproval of what these kids are getting up to in Fast Times must have jarred with the times? (Indeed, everyone should check out Roger Ebert's one-star review of this movie: a fascinating read about a fascinating mis-read of a classic movie.)

Fast Times’ kid’s-eye view of high school was something new, after a decade’s worth of movies and TV shows like American Graffiti, Grease, and Happy Days that had popularized a nostalgic gaze on an earlier generation’s teenagehood.[…]

[Director Amy Heckerling's] semiautobiographical romantic comedy I Could Never Be Your Woman languished on a shelf for nearly two years before its release in 2007 […]. As Heckerling put it in one interview, “If they didn’t have the results that they wanted, that wasn’t like, ‘We didn’t develop that movie right’ or ‘That wasn’t the right person to be in it,’ or any of that. It was always ‘Well, it was women.’”

[…]

It was almost a decade later, under the presidency of George H. W. Bush and amid a renewed push to overturn Roe v. Wade, that I would go into a clinic for my own abortion. I remember being mad at myself for getting into that situation—unlike Stacy, I was old enough to have been more careful—but, thanks in part to Heckerling’s pragmatic treatment of the subject all those years before, I felt no fear, guilt, or shame. Getting pregnant and not wanting to be, Fast Times had taught me, was a normal, even common occurrence; the most important thing was having someone who loved you to drive you home afterward.

— Dana Stevens (Criterion)

If this movie had been directed by a man, I'd call it sexist. It was directed by a woman, Amy Heckerling — and it's sexist all the same. It clunks to a halt now and then for some heartfelt, badly handled material about pregnancy and abortion. I suppose that's Heckerling paying dues to some misconception of the women's movement. But for the most part this movie just exploits its performers by trying to walk a tightrope between comedy and sexploitation.

Some, maybe even most, of the film’s characters are selfish and inconsiderate, but there are no villains here, and even the most humiliating spectacles on display are handled with an assurance that these are the awkward, soon-forgotten stumbling blocks of adolescence. […] Perhaps the film’s greatest insight […] is the extent to which young adults during a consumerist boom time substituted their lack of life experience and self-awareness by presenting personalities shaped by popular culture. All of the film’s major characters have a distinct way of dressing that instantly reveals their true personalities, and they pay for the accoutrements that define them with jobs in the mall where they spend their wages in a sort of “Möbius strip” economy. […] [Fast Times] infuses the typically tossed-off construction of the teen comedy with a real feel for fading adolescence, even while wallowing in the playful immaturity of its characters. Though not blind to the occasionally harrowing pitfalls of youth, the film remains optimistic in its sense that high school isn’t the best time of our lives, but rather the time when one is most free to make mistakes.

— Jake Cole (Slant Magazine)

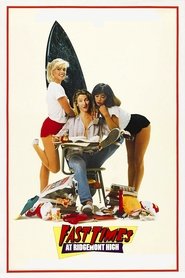

Synopsis: Based on the real-life adventures chronicled by Cameron Crowe, Fast Times follows a group of high school students growing up in Southern California. Stacy Hamilton and Mark Ratner are looking for love, and are helped along by their older classmates, Linda Barrett and Mike Damone. Jeff Spicoli, a perpetually stoned surfer faces-off with the resolute teacher, Mr. Hand. Hilarity and heartbreak ensue.