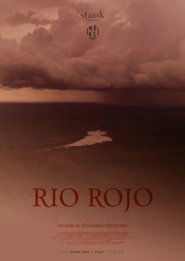

Cambridge Film Festival 2023: Film #9

Disguised as a nature documentary, Río Rojo is torn between depicting the river as an abstract object of beauty and a site of politics, a tributary in the unfathomable hyperobject of ecological change. What becomes quickly clear is that this starkly attractive film presents a challenge to Anglo-American audiences, who still remain mostly ignorant of over 50 years of armed struggle by the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia. Yet this short film is perhaps stronger as a result for it thereby serves as an implicit rebuke to our insularity and parochialism.

Not surprisingly, my two favourite scenes revolve around its politics. The first is when the husband and wife are impassively listening to the latest news about the FARC through the radio. To this viewer at least, this felt like a realistic view of how most people in the world hear of information that affects them, instead of treating it as a varietal of entertainment. The other scene that I can still recall is when the local mayor (?) is talking up how good it is that tourism at the Caño Cristales can now resume. The villagers, knowing in their gut what this means, look on without comment, and the mayor is tellingly cut off mid-sentence by the film's edit. Indeed, one of the strengths of this documentary is that it doesn't demand that the villagers can evince a coherent worldview on-demand: their lack of classical erudition and geopolitical perspective doesn't devalue their opinion. I'm torn about the few inexpensive (but fairly low-key) jibes at the tourists, though — one scene has a visitor asking for a Coca-Cola that, I believe, the film is treating a little scornfully, and deploying Coca-Cola as a symbol of the harmful effects of modernity was a little heavy-handed even for something as delicate as Ozu's Late Spring (1949).

In his pre-recorded introduction, director Guillermo Quintero expressed surprise that pollution and deforestation around the river has actually accelerated since the Havana negotiations of 2016. It is unclear whether Quintero was being ironic, for if there was anything that was eventually going to bring about some semblance of stability in the region, it was going to be global capitalism and the seemingly relentless drive to extract its natural resources in a multipolar world.

Synopsis: In the Serranía de la Macarena, in the north of the Colombian Amazon, lies “Río Rojo”, a mythical river that runs through the middle of the forest, also called “the river of the seven colors”. Young Oscar, grandmother Doña María and the Indian Sabino live peacefully in the region, in communion with nature. But this area, once preserved by the conflict with FARC, is now victim of its beauty and threatened by the arrival of new visitors…