The film shows the happy endings of earlier westerns were sham: the savage outlaws can come back at any time, and the extras who benefited from law and order decide they'd rather be kicked around by Miller than shot dead. This enraged Howard Hawks and John Wayne, who responded with Rio Bravo (1959), in which a Marshal turns down offers of help because he's being paid to do a job and doesn't want innocents killed. Wayne was proud of getting the blacklisted Foreman kicked out of America in revenge for the "un-American" gesture that ends High Noon, though [he] said he wished someone would write him a western part as good as Will Kane. Many commentaries on High Noon have assumed that it's making a statement about the bullying tactics of Senator Joe McCarthy […]. However, it's possible McCarthy might have seen the film as an endorsement — identifying with Cooper, a real-life supporter, and thinking of the townsfolk as the fellow travellers and liberals whining about his crusade against creeping subversives like Frank Miller.

— Kim Newman (Empire)

Zinnemann was classical Hollywood’s own Ang Lee—that is, a fastidious journeyman director who rarely, if ever, worked in the same genre twice, and whose devotion to expectations and professional comportment paradoxically make it both easy and hard for anyone to dismiss him simply as an order-taker. […] His direction of High Noon seems resolutely by-the-book, only it’s a book that never existed, but even if the expressionist punches he throws seem somehow impersonal, and secondhand, he still lands more than he misses.

— Jaime N. Christley (Slant Magazine)

Eisenhower screened High Noon three times at the White House. According to White House logs, High Noon ranks as the movie subsequent presidents would most request—none more than Bill Clinton, who watched his favorite film some twenty times and told Dan Rather that he'd recommend the Wester to his successor as a text. Unfortunately.

— J. Hoberman: Film After Film (Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema?) (2012)

Though the hero of High Noon proves him– self a better man than all around him, the actual effect of this contrast is to lessen his stature: he becomes only a rejected man of virtue. In our final glimpse of him, as he rides away through the town where he has spent most of his life without really imposing himself on it, he is a pathetic rather than a tragic figure.

— Robert Warshow: Movie Chronicle: The Westerner (1955)

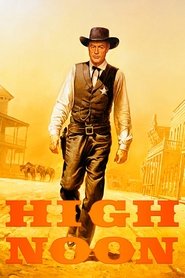

Synopsis: Will Kane, the sheriff of a small town in New Mexico, learns a notorious outlaw he put in jail has been freed, and will be arriving on the noon train. Knowing the outlaw and his gang are coming to kill him, Kane is determined to stand his ground, so he attempts to gather a posse from among the local townspeople.