Often called one of the last of the great 1970s pictures, Cutter's Way was released at a time when New Hollywood movies such as this were, in the words of Adam Nayman:

... an endangered species in a Hollywood that sought to either cozily infantilize its viewership by awakening the proverbial “inner child”—the unspoken mission of Star Wars and the deliberate platform of E.T.—or service a growing adolescent constituency desperate to see itself enshrined onscreen.

Adam is perhaps missing mainstream audience's desire to see superficially apolitical films after a decade or so of rather bummer movies like The Conversation et al. Sure, the release of Heaven's Gate (1981) didn't help affairs, but still, I prefer to blame LucasFilm.

What's curiously weak in Cutter's Way, is the character of the sister of the murdered girl. She seems strangely implausible, and likely entirely superfluous to the plot. She certainly doesn't influence what Alex Cutter actually does in any way, although I suppose that's part of the point of Cutter. It could be said that she gives moral license to Cutter's actions, but that doesn't seem to fully justify why she's there in the first place, beyond, perhaps, being a 'fourth wheel' in the threesome of Cutter, Bone and Mo. Similarly weak is the explicit references to Moby Dick in the first act. Cutter's Ahab-like behaviour didn't need to be signposted so crassly to the viewer like that.

The film leaves in plain sight the implication that everyday people are as responsible for the state of things as events beyond their control. The question of Cord’s guilt is ultimately incidental, as the evidence for and against his culpability collapses against Cutter’s single-minded desire for revenge against anyone who made it out of the ’70s in better shape than when they went in.

This is a story about seeing clearly, for one thing, and the [opening] parade shot forces us to peer into a hazy, mundane image and search for something sinister within it. [It's] a film about ambiguity, and that opening shot delivers the mood. We're not sure what we're seeing, or how it fits into the story. But something mysterious has begun, and when that white dress wipes away one image and presents another, it's like a curtain being pulled on a special place. Something is coming toward us—and this is also true in the film's devastating final shot, where something comes toward us that utterly finishes the film but also opens up a world of possibilities. And by that point we can't back away.

— Robert Horton (RogerEbert.com)

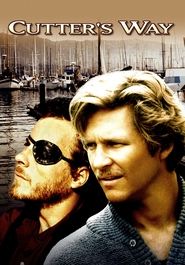

John Heard, then almost unknown, is Cutter, a showy, noisy part, while Jeff Bridges has the quieter, more difficult role of Bone. The truly unforgettable performance comes from Lisa Eichhorn as Cutter's abused and defeated, hollow-eyed alcoholic wife Mo, the soul of the movie, delivering [her lines] in her thin, cracked voice.

— John Patterson (The Guardian)

Cutter could be right, or his fixation could be a final expression of existential boredom and despair, a frantic search for meaning and justice in a leisured, prosperous American society in which Cutter's traumas and sacrifices on the field of battle are meaningless.

— Peter Bradshaw (The Guardian)

Alex reminds others that he is a veteran, which is to say that he is mostly reminding himself.[…]

Cord may have murdered the teenage girl hitchhiking home from the disco, but Cord Consolidated Oil is what sent Alex to war. One can be blackmailed and prosecuted; the other will never be held accountable.

— Tova Gannana

Synopsis: Alex Cutter is a boozy, belligerent and deeply cynical Vietnam veteran whose encounter with a landmine during the war has left him minus an eye, a leg and an arm. When his drifter playboy friend Richard Bone is falsely accused of murder, Cutter sets out for revenge in his own inimitable style.