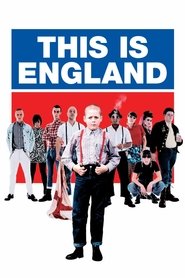

Modest, ostensibly uncomplicated and not superficially didactic, Shane Meadows' This Is England communicates something of the nexus between notions of fatherhood, nationality, nationalism, friendship groups, gangs, the National Front and the far Right in the 1980s. And does so by employing and yet also eschewing the commonplace motifs and imagery commonly deployed in contemporary montages of that time that tend to frame those prevalent notions as aesthetic trends and/or attractions now alien to Britain in the 2000s.

Whilst patently an abstract allegory of England and 'Englishness', This Is England also manages to concretely convey some of the key contradictions of these overlapping ideas. It's commonly said in relation to this film that skinheads were 'actually' started as a Jamaican reggae-loving group that was fated to be co-opted by the National Front. Many other examples abound, underscoring my long-held belief in the severe diminishing returns inherent in pointing out hypocrisies of and on the political Right. Yet the contradiction that first stood out to me is the rather pat observation that the first flag that we see in This Is England is not an English flag at all. (It's interesting to note that 'even' Powell & Pressburger messed this up with a similar imprimatur of 'Made In England' attached to their Canadian and Scottish films.)

Just as François Truffaut's The 400 Blows cloaks its politics through the veil of a genuinely believable child protagonist, so does Made in England connect and indite the initial wave of market-oriented reform policies as experienced under Thatcher's government and its concomitant deindustrialisation with the rise of nationalism. Given that the Right today is still saying variations on the "These days…" meme, the National Front leader Lenny (perhaps the film's besuited allegory for Capital in the Marxist conception of fascism) suggests that "We can't even say the word English anymore".

That final word "anymore" in particular, strikes an interesting note when watching a film in 2024 that was originally released in 2007 ... itself based on events in 1983. What did this mid-2000s film say about how we felt about the 1980s in 2007? Before the 2008 financial crash and the austerity that has desaturated the 'long' 2010s of 2008 to the present day, did Britain in 2006 sincerely contend that New Labour had fixed all those rotten planks on Shaun's boat that he returns to at the end the film?

Its subliminal politics aside, this film would be nothing without its strong performances. Joseph Gilgun is underrated as the schematic-yet-not-obvious opposite of Combo, and he plays as a kind of post-Clockwork Orange leader of his platoon... albeit with a much more benevolent mien than Anthony Burgess' Alex: "There was me, that is Woody, and my three droogs making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening." And Stephen Graham plays the part of the inarticulate romantic fascist particularly well in the scene in his car outside the biscuit factory, which incidentally suggests that Combo subconsciously yearns for a son — itself hinting at why (fatherless) Shaun is drawn to him and why Combo was transfixed by Shaun's appearance at the earlier party. Equally underrated is the editing, which, save for the overextended final five minutes that merely recapitulate the previous fifteen (and includes the shopworn idea of 'throwing the thing I now disown into the ocean' imagery), manages to convey the general tenor of the racial insults and abuse without granting the words their complicated violence of representation.

His mother […] marches Shaun down to the cafe where the gang hangs out, wants to know who did this to her son and asks, "Don't you think he's a little young to be hanging around with your lot?" Then, curiously, she leaves Shaun in their care. You could spend a lot of time thinking about why she does that.