For another homoerotic story about a love triangle in the world of sport and competition, see, of course, Luca Guadagnino's Challengers (2024).

Suggestive dialogue and eye contact give the impression that there’s a history of intimacy between Skinner and her coach; clocked by Cahill, this unspoken erotic tension will contribute to her growth. The viewer is left to project whether there’s jealousy involved or whether Cahill simply wants to belong with Skinner, Tingloff, and/or the intimacy they share, which may be what Cahill desires: an intimacy with track and field.[…]

Overwhelmed by lesbianism, which is far from the main action of the film, the press were titillated to distraction—or were trying to sell their publications with sex. Men described steam room scenes. Feminists did as well, flagging “the male gaze.” Gays debated whether the film was gay enough; it’s calmly bisexual in a way that only Gen Z may be as a cohort ready for, though they’ll need a trigger warning for the racist and homophobic jokes that serve as the film’s set dressing.

[…]

Cahill is like a Hayao Miyazaki heroine, an innocent on a journey of becoming, with her innocence extending to a bisexuality that is never abject, violent, victimized, or shame ridden, as Hollywood relies on, with regard to femmes, to capitalize on attention.

[…]

[The film] serves as a meta narrative for its own creation and how Hollywood functions. Robert Towne is to Personal Best what Coach Tingloff is to his trainees: the male pseudo-authority and the saboteur whose simultaneous elevation and degradation of the women under his charge, his identifying with them and lusting after them, precipitates his own irrelevance.

[…]

One wonders if [Towne's] downslide was not deliberate, similar to Cahill’s foundering when her father coached her. Did Towne martyr himself? [In] his film’s end, the women win a place in the Olympics, but the games are canceled; Towne made a masterpiece that was destined to flop at the box office. As if he knew the rigged game he was playing, the moral of his movie is that winning is fleeting and the best you can ever do, as Cahill’s boyfriend [tells] her, “is whip your own ass.”

— Fiona Duncan (Gagosian Quarterly)

Mr. Glenn does have the film's single, truly funny speech, in which he compares the duties of a women's coach to those of the coach of a men's professional football team. […] Mr. Towne treats the story of the lesbian love affair with something that passes so far beyond understanding that it begins to look like undisguised voyeurism. Personal Best is nonjudgmental in the way that a porn film is nonjudgmental about the activities of its performers.

— Vincent Canby (The New York Times, 1982)

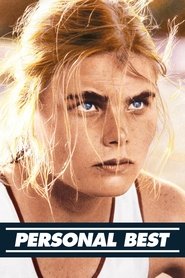

Synopsis: Young sprinter Chris Cahill is having difficulty reaching her potential as an athlete, until she meets established track star Tory Skinner. As Tory and her coach help Chris with her training, the two women form friendship that evolves into a romantic relationship. Their intimacy, however, becomes complicated when Chris' improvement causes them to be competitors for the Olympic team.