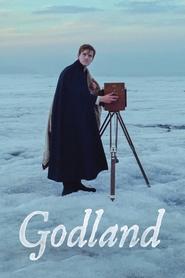

[Director] Pálmason’s unifying theme is the egocentrism and inevitable violence of masculinity, which is linked in Godland to colonizing efforts and the blinkered rendering of history that results from it via Lucas’s photographs. It’s well-covered terrain, but [Pálmason] undercuts the preordained spiral of one flawed male protagonist with the confrontations of forces greater than himself—in this case, Iceland’s forbidding vistas and a community of real people who challenge Lucas’s smugly held assumptions about faith and morality—and the repercussions of his actions on others.

— Carson Lund (Slant Magazine)

A story about the willful blindness of colonialism, and one that benefits from Pálmason’s own dual-layered identity as an Icelandic-born filmmaker who spent many years studying and living in Denmark. From the opening scene of Lucas receiving his instructions from an older priest, there’s a clear, if understated, tension between the Danish ruling powers and what they assume to be their untamed island subjects, so desperate in their need for order, civilization and God.

— Justin Chang (Los Angeles Times)

[Ingvar E.] Sigurðsson only hints at the depths of Ragnar’s emotions, that’s also what makes his behavior so attractive. Both men have an inner life that’s only partly revealed through episodic scenes that take place around the church and Carl’s home. But [director] Pálmason’s latest movie comes to life whenever its characters struggle to retain their humanity and poise in the face of great, largely implied despair.[…]

The Icelandic locations do a lot of talking for Pálmason’s characters, and they tend to speak more forcefully than either Lucas or Ragnar. Still, the big emotional finale of Godland is less ambiguous than one might hope for, given how much of this movie isn’t about the story, but rather the in-between moments when we struggle to be better than our past actions. The climax of Godland feels conclusive in ways that the rest of Pálmason’s mystery play does not, making one wish that there was an extra hour or two between its beginning and the very end.

— Simon Abrams (RogerEbert.com)