Really respect how much is unsaid in this film. It's interesting to ponder that it often feels like it is Lucien's clothes that give him strength or armor, and not the submachine gun. I would perhaps quibble that Aurore Clément's 'France' is too allegorically named if Claire Denis didn't show how effective that can be in her 1988 Chocolat. Very interesting how so many of the film's contemporary reviews reference My Lai.

The movies, with their roots in stage melodrama, have conditioned us to look for evil in social deviants and the physically aberrant. The pornography that Malle delves into makes us think back to the protests of innocence by torturers and mass murderers—all those normal-looking people leading normal lives who said they were just doing their job. Without even mentioning the subject of innocence and guilt, Lacombe, Lucien, in its calm, leisurely, dispassionate way, addresses it on a deeper level than any other movie I know.[…]

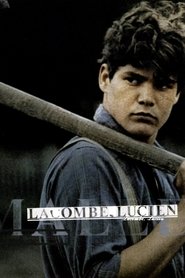

The schoolmaster is right [in] perceiving that Lucien is apolitical and unprincipled—that he just wants some action. Lucien is good to his mother, and in normal circumstances he would work on a farm, taking care of his own and not bothering anybody, and he’d probably be a respected, unconscionably practical member of the community. But in wartime, he’s a perfect candidate for Nazi bullyboy. [The] answers to our questions about how people with no interest in politics become active participants in brutal torture are to be found in Lucien’s plump-cheeked, narrow-eyed face, and that showing us what this boy doesn’t react to can be the most telling of all.

[…]

Throughout the film, this Gestapo hotel-headquarters recalls the hotel gathering places in thirties French films, yet it has an unaccustomed theatricality about it. [They're] much like the ordinary characters in a French film classic, but they’re running things now. The hotel is almost like a stage, and, wielding power, they’re putting on an act for each other—playing the big time. Nazism itself (and Italian Fascism, too) always had a theatrical flourish, and those drawn into Gestapo work may well have felt that their newfound authority gave them style.

[…]

There is nothing admirable in Lucien, yet we find we can’t hate him. We begin to understand how his callousness works for him in his new job. He didn’t intend to blab about the schoolmaster; he was just surprised and pleased that he knew something the Nazis didn’t. But he’s indifferent when he witnesses the torture, and he shows no more reaction to killing people himself than to shooting a rabbit for dinner or a bird for fun.

— Pauline Kael (Criterion)

[This] film isn't really about French collaborators, but about a particular kind of human being, one capable of killing and hurting, one incapable of knowing or caring about his real motives, one who would be a prime catch for basic training and might make a good soldier and not ask questions.

Synopsis: In Louis Malle's lauded drama, Lucien Lacombe is a young man living in rural France during World War II who seeks to join the French Resistance. When he is rejected due to his youth, the resentful Lucien allies himself with the Nazis and joins the Gallic arm of their Gestapo. Lucien grows to enjoy the power that comes with his position, but his life is complicated when he falls for France Horn, a beautiful young Jewish woman.