The zombie/apocalypse/dystopia genre has always had a rather libertarian tendency to instinctively treat other people as walking, talking liabilities, but it took the conceit of the Quiet Place franchise to make the latter so explicitly literal.

No doubt this anti-communitarian attitude lingers in all cultures to a certain degree, but is it possible to suggest that this is an especially American tendency? Notwithstanding the British 28 Days Later (2002) exists, and that on both sides of the pond the term "populist" is, as a rule, a term of opprobrium, it is surely the case that the US tends to venerate the myth of individual above the collective, the elite posse above the mob, and the rights of states above those of the Federal government. This overarching tendency is even built into the venerable US Constitution, where the makeup of the Electoral College, the Senate and who makes the appointments to the judicial branch lies somewhere on the spectrum between undemocratic and anti-democratic depending on your personal politics. Indeed, in the words of Corey Robin, "a central purpose of the document is to check majoritarian government, giving a small group of elites the power to thwart the will of the democratic majority." It seems doubtful that this is simply just sensible and safe outcome case of reasonable political science on the part of the founders and framers, but one of instinctively, gut ideology: recall that the darling of liberal Broadway, Alexander Hamilton, whilst having dinner with John Adams, slammed his hand on the table and declared: "Your people, sir — your people is a great beast!"

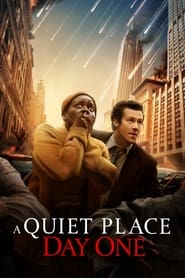

All that aside, whilst I enjoyed parsing the reactionary and anti-communitarian politics lurking just below the surface of the two previous instalments, this one was a little less engaging for all sorts of reasons. The references to 9/11 and/or Spielberg's The War of The Worlds seemed, at best, co-incidental, for they added neither depth nor NYC specificity to this particular story at all. Ditto Eric's nationality: what did it mean that he was British beyond the distracting paratextual implications that the film was (at times quite obviously) filmed in London and a British character was likely needed to get a tax break? Similarly, Simara's cancer was devoid of allegorical or metaphorical connotations beyond giving the film's narrative a reason for her to do thuddingly stereotypical "I heart New York" things like loving Harlem jazz, wanting "a slice of pizza" and also confidently stating where the "best slice of pie in the Big Apple" can be had. Surely even hardened New Yorkers cringe when people say that? (Almost equally cringey was the Nina Simone needledrop just before the credits.) Finally, even I know that you should rarely, if ever, actually show The Monster on screen, yet Day One seems to have hundreds of the things at once without pausing to consider how this erodes the alien's literal and figurative power.