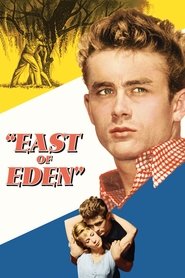

I've never really got the James Dean cult, so it's somewhat reassuring that even some contemporary reviewers did not see it either. Like Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, their tragic (and tragically early) deaths no doubt did a lot of work in ensuring these flames would burn forever. (Just imagine if The Beatles all died together in 1969.) But as Dan Callahan astutely suggests, just like Monroe and Presley, it is "in still photos that the Dean legend is most potent and most understandable", and was a time before repertory theatres (and streaming, obvious) that could not easily pull up films from 1955 to observe the steak unmediated through the sizzle of magazines.

In simplistic ’50s fashion, we have “Daddy loves me, so I’m good” and “Daddy doesn’t love me, so I’m bad.” This unfortunate naïveté, founded in psychoanalysis and based on blaming parents for everything, persists to this day.[…]

in East of Eden [James Dean is] doing a Brando imitation deepened by his own aggressive need to charm every man, woman, child, and dog around him. Dean even tries to charm plants: [Dean] does a dance around the crops and talks to them as if they were a lover. His miming of vulnerability is hair-raisingly calculated. [And] whenever he talks, he’s doing his extravagantly mannered idea of Brando: taking pauses for no reason, hesitating over words, repeating words, scratching himself, pulling his ear, mumbling. Meant to be naturalistic, his performance here seems incredibly self-conscious, even in the famous moment when he tries to give his father money and explodes in frightening, far-out grief

[…]

[It] all finally seems to have more to do with acting than with anything else the movies are supposed to be about. A whole subplot in East of Eden about World War I and prejudice against Germans is especially tin-eared and crude.

— Dan Callahan (Slant Magazine)

This young actor [James Dean], who is here doing his first big screen stint, is a mass of histrionic gingerbread.He scuffs his feet, he whirls, he pouts, he sputters, he leans against walls, he rolls his eyes, he swallows his words, he ambles slack-kneed—all like Marlon Brando used to do. Never have we seen a performer so clearly follow another's style. Mr. Kazan should be spanked for permitting him to do such a sophomoric thing. […] In short, there is energy and intensity but little clarity and emotion in this film. It is like a great, green iceberg: mammoth and imposing but very cold.

— Bosley Crowther (The New York Times, 1955)

Synopsis: In the Salinas Valley in and around World War I, Cal Trask feels he must compete against overwhelming odds with his brother for the love of their father. Cal is frustrated at every turn, from his reaction to the war, how to get ahead in business and in life, and how to relate to his estranged mother.