Malick should 'remake' other Disney classics. How about Robin Hood?

Upon exiting my second viewing on a cloudy matinee Sunday, I found that Malick’s vision had rendered our world drab and cheap—as [if] Captain Christopher Newport’s (Christopher Plummer) warnings to his fellow settlers in the film had fallen on deaf ears, allowing America to grow up stunted, deformed, tainted, and gross. In short, into the world we inhabit today.

— Jeff Reichert (Reverse Shot)

Pocahontas travels to England with a few kinsmen, and the sight of the Americans, resplendent in skins and feathers, shivering proudly amid topiary and gravelled walks is at once witty and sublime. The lesson is as clear as rainwater: to the innocent eye, ripe for marvelling, every world is new.

[Malick's] often breathtaking images may conceal the radical nature of his filmmaking, since in the modern era, serious art often prefers the discordant or the everyday, and avoids the comfort that “lovely images” seem to offer. But rather than reassuring, Malick’s images inspire the awe associated with the sublime, which the Romantics defined as the beauty that springs from terror. If we probe them, they deeply unsettle us.[…]

The New World shows that the first impulse of European settlers in America was to enclose space rather than to dwell in its openness. As much as Malick understands this impulse as tragic, he envisions more than a return to nature as a response.

— Tom Gunning (Criterion)

It’s telling that the first thing we see the British erect upon landing isn’t shelter, but a noose, and for all the paranoia the British feel toward the Powhatan, it’s the Westerners who resort to barbarism, torture, and cannibalism as starvation and fear of the unknown overtake them.[…]

Corsets and textbooks become weapons as much as cannons and muskets, and by the time Pocahontas arrives in London as a curio to raise interest in the colony, the once unbound young woman seems no different than a caged animal. The only liberation from this life is death, which Malick films with brio, charting the transmigration of the woman’s soul back to her home with the aid of Wagner and a barrage of ecstatic imagery.

— Jake Cole (Slant Magazine)

Terrence Malick risks his entire story to make us feel his characters’ uncertainty. Having established the movie’s Plan A, he drops it, and the movie is suddenly adrift, wallowing in pity for unrequited love. Eventually a Plan B emerges, but as a viewer I resisted it, and so does Pocahontas. Surely Plan A can be salvaged! But Malick, determined to leave it behind, changes the identity of his main character and asks us to begin again, from scratch

— Robert Davis (Paste Magazine)

The events in his film, including the tragic battles between the Indians and the settlers, seem to be happening for the first time. No one here has read a history book from the future.

For the filmmaker, who is more poet than historian, Pocahontas is clearly a metaphor (virgin land, as it were), but to see her as exclusively metaphor would only repeat history's error. What interests Mr. Malick is how and why enlightened free men, when presented with new realms of possibility, decided to remake this world in their own image.[…]

In the past, Mr. Malick's fondness for voice-over has sometimes seemed like a crutch, symptomatic of a weak screenplay, as in his last film, The Thin Red Line, or as a misplaced bid at naïve consciousness. Here, though, you feel as if you are eavesdropping inside the characters' heads. While Pocahontas's voice-overs are filled with schoolgirlish yearning, Smith sounds dangerously lofty, as if he is rehearsing the dissembling that will shape his later histories.

— Manohla Dargis (The New York Times)

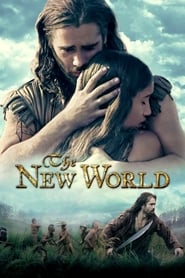

The New World takes a shopworn American myth—the first encounter of settlers and Indians at Jamestown, and the romance between Pocahontas [and] Capt. John Smith—and runs it through the Malick-izer, making it feel rich, strange, and new.[…]

The Smith/Pocahontas affair is like the erotic equivalent of the Thanksgiving story: It is true as a metaphor, a condensation of fantasies about colonization and first contact.

[…]

Part of the story he’s trying to tell is about how the process of miscegenation inevitably invites us to construct such Edenic myths. Malick is obsessed with Eden or, perhaps more precisely, obsessed with America’s obsession with it. All of his films contain these paradisiacal, usually erotic interludes. But even as the lovers cavort in their makeshift treehouses or smooch by the river, they realize that their idyll is fragile, threatened by the imminent reality of work, or winter, or war.

— Dana Stevens (Slate)