I'm not sure I've ever seen New York look this awful. Whilst the city certainly looks shabby in Chantal Akerman's News from Home (1976) and even worse in Walter Hill's 1979 The Warriors (to take just two rather contrasting films), there's a way in which that Cassavetes shoots New York which makes the city's grime looked lived in as well. Everything (and everyone) now looks so acclimatised and habituated to the dilapidated nature of the city's architecture and public services that it is somehow even more depressing than outright grime.

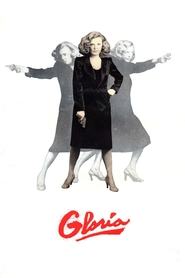

This nicely extends to its social architecture as well. Gloria is undoubtedly a vehicle for Gena Rowlands but with an undeniable subtext about the want of any social cohesion in 1980s New York. This theme feels stronger than the 'found family' narrative floating on the surface, and the film feels more like a cry for a more communitarian spirit in peak-crime-era NYC than a call for a more flexible approach to the nuclear family. While the tension in the film might ostensibly reside in whether Gloria will take to (and take in) Phil or not, anyone who has seen a film before will know that she will inevitably do just that. Instead, the driving motor of Gloria is the unstated notion that the Mafia, the ostensible bad guys from beginning to end, are more of a family (or 'community' if you will) than the strangers we pass on the street every day. Or the bartender who serves us a 'cold' (tm) beer at the bar at 8:30 in the morning.

To be sure, the tension also resides in the almost complete omission of Gloria's backstory, granting her a sense of mystery that proves to be completely, well, earned. This elision seems to fit her character: she doesn't have to prove herself to anyone she encounters within the film, so why should her character have to be explained to the viewer either? (Incidentally, the word 'dame' is no longer thrown around as much as it was, but it fits the character of Gloria almost as well as a cigarette fits in her mouth.) Introduced as simply a neighbour, Gloria turns out that... well, the point of the script is undoubtedly that even in such a big city as New York, we aren't really strangers after all. The least we can do is help each other when our groceries spill out on the bus. It seems somehow an especially Cassavetian touch that the Black taxi drivers are so helpful, and, in many cases, not even charging her.

Indeed, as a Brit, questions of race are not always at the forefront of my mind. Screened just a fortnight after the death of Gena Rowlands, one of the biggest laughs in the audience at my local arthouse was when Gloria says to Buck Henry that she doesn't like kids, adding, "especially your kids". It's edited in a way that really catches the eye, with the camera never leaving the (biological) mother's face. The tenor of the laughs struck me as responding to the joke revolving around the old saw that nobody likes other peoples' kids. Ho ho. But in retrospect, I now realise that the camera may have been lingering on the mother's face because she is Puerto Rican (i.e. "your kids"), and therefore the "will she, won't she" drama between Gloria and Phil in the rest of the movie is also a story of Gloria coming to terms with his race, rather than Gloria 'not' wanting a kid at all. No doubt any Americans watching would have found our naïveté about New York's racialised ghettos endearingly cute.

ps. Isn't it a bit weird how the film's setup eerily mirrors Léon: The Professional (1994)?