— A girl like that would raise a dead man.

Low-key hilarious, especially in the sequence in which El Hadji is disgraced in the Chamber of Commerce. He isn't allowed to speak in Wolof by the President, but must speak in French: "Even the insults; in the purest French-speaking tradition." The icing on the cake is when after his briefcase is taken away from him (the shame!), a new member is immediately introduced, who the viewer recognises as the pickpocket who struck it lucky earlier in the film. Whoever said postcolonial studies was dusty and boring?

[Sembene] bitterly implies a continuing European influence in the former colony. The white man who brought the briefcases – a slight, sinister little man with a mustache and dark glasses – is constantly at the side of the country’s new president, but never says a word. Sembene obviously implies that he doesn’t need to.

Animal Farm applied to Africa independence.

— Richard Eder (The New York Times)

El Hadji needs the blessing of the villagers, of the elders, of those he has wronged, to move forward in his own life. This perhaps explains the serene look on El Hadji’s face, captured in the freeze-frame. He is in the process of confronting the past, which has the potential to brighten his future. To gloss and pervert Albert Camus’s famous reading of the myth of Sisyphus in which acceptance of the absurdity of the human condition brings contentment, one must imagine El Hadji happy.[…]

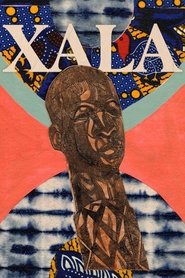

As she enters the office, Rama wears a multicolored boubou and jewelry meant to accomplish two goals: first, to oppose her father’s bland European suit; and second, to blend into the purple background provided by a map of Pan-Africa, with no discernable country borders. Past (as traditions and as previously established Pan-African ideals), present (Rama herself), and future (will she be the one to lead the continent to a utopic borderless Africa?) coalesce once again.

— Vlad Dima: Everything Begins in the Middle: Xala and Futurity (Film Quarterly)